Genealogien Arbeiten von Uli Westphal

June 4th – October 11th 2009

The works of Berlin

artist Uli Westphal are closely related to Biology and its

classification-systems, but set emphasis on different subject matters.

For example, instead of showing the genealogy of elephants, he

visualizes the development of their depictions. The works stand in a

dialog between culture and science. He poses questions on how nature is

perceived, depicted and understood in these different contexts. His

works derive from collections, simulations, animations and

classification-systems. These are based on actual, existing, natural

phenomena, but they tell most of all about the development of human

conceptions of nature.

A peculiarity of this exhibition is the

integration of three of Westphals works into the permanent exhibition

of the museum.

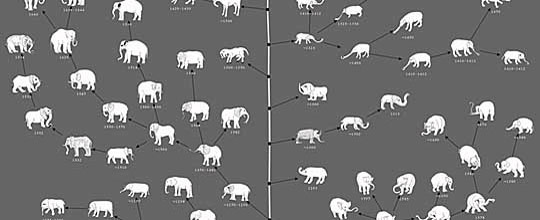

The work Elephas Anthropogenus investigates the depictions that Western-Europeans have made of the elephant during the course of history.

Since there was no real knowledge during the middle ages, of how this

animal actually looked, illustrators had to rely on oral and written

transmissions, to morphologically reconstruct the elephant - thus

reinventing an actual existing creature. This led to illustrations that

still show the basic features of an elephant, but that otherwise

completely deviate from the actual appearance and body shape of this

animal. Based on a collection of such depictions, the work traces the

evolution of Elephas Anthropogenus,

the man-made elephant. The result is a genealogical tree diagram, in

which the imagery is arranged according to taxonomic aspects.

In

this case Westphal uses the visual language of natural science to give

form and structure to the development of a cultural image of nature.

The work Mutatoes deals with contemporary perception of nature. The Mutato-Archive

is an extensive photographic collection of non-standardized fruit,

roots, fungi and vegetables. Edible plants have developed, especially

due to the industrialization of agriculture, into organisms whose

morphology is shaped by societal ideals of beauty and perfection.

Today we have a clearly defined idea of how, for example, an apple or a tomato should look.

We encounter variations and deviations from this well accustomed norm mostly with mistrust.

Westphal uses the word 'mutatoes' as a collective term that comprises

all produce that contradicts these optical guidelines. The aggregation

of these specimens into a larger collection reveals the strict borders

that man has drawn between the cultivated and the wild.

The Mutato-Archive

serves to remind us of the great variety of shapes that, as a

consequence of this segregation, fall into oblivion until they

eventually disappear.

The work Coleoptera is an animation produced by the fast

progression of over 2000 silhouettes of different beetle-species. The

individual beetle silhouettes are sorted according to their

body-shapes, so that the slight variations in their appearance create a

raw impression of movement. The different species turn into a single

but constantly transmutating organism.

Beetles form the biggest order of insects and account for about 25% of all described species.

The work Coleoptera

is an attempt to make the immensity of this biodiversity

comprehensible. It does so by using a purely visual, and therefore

rather subjective classification.

The work is a collaboration with the American artist Kristen Cooper.

The work Chimaerama is a sort of random generator that

recombines segments of hundred Victorian animal-illustrations into one

million new creatures. A 22 hour long film shows these combinations at

a rate of 12.5 images per second. This flow of images can be paused by

means of a switch - like in a slotmachine - and the chimera that was

generated in this moment becomes visible.

The work refers to elements from zoology as well as from the history of science:

In past centuries, people used to describe a new found animal-species

by combining the body parts of already known animals. A sea lion, for

example, was described as a dog with feet like those of a goose and

skin like that of an eel. As a generator of novel lifeforms, the work

also deals with crossbreeding as a driving force of evolution: The

constant shuffling of genetic makeup forms a major aspect of

evolutionary processes.

Westphals

works show that the need to structure the world, to group things into

classification-systems and families is not only a peculiarity of the

natural sciences. These mechanisms help us to understand the complexity

of the world and to divide it into smaller, more manageable entities.

They can therefore also be used in cultural contexts as tools of

cognition. These systems however, remain artificial constructions,

whose forms are dependent on the meaning and function that we give

them.

Westphals works integrate themselves very well into the

context of the Phyletisches Museum, which was founded by Ernst Haeckel

as a place dedicated to the meeting of art and science.

More Informations on the artist and the exhibited works can be found here.